Why Lipid Nanoparticles are Colloidal Multi-Particle Systems (English Transcript of my new Youtube Presentation)

And why traditional ADME models, based on mass assumptions and total dose, will fail

To be on the safe side and avoid errors in the script for automatic translation, I translated the entire script.

At this point, as a response to the hopefully constructive discussion with Dr. Kremer, I would like to clarify a few things and deliver a rather dry technical lecture that may finally resolve some misunderstandings and show why Dr. Kremer and I were in fact talking about two completely different things.

Regarding the effects of modRNA, we—the authors (me, Maria Gutschi and Dr. Stephanie Seneff) of the papers shown here—see it similarly to most critical scientists: it already has considerable disruptive potential. However, we argue against the oversimplified assumption that modRNA itself is the root of all evil.

Quite the opposite: when we speak of LNP-modRNA injections, we can only speak of LNP-modRNA. The translated spike protein merely acts as an additional accelerant on top of this, amplifying various pathogen-like mechanisms.

In short, we are dealing with very complex, dynamic colloidal particle systems.

But what exactly are self-assembling, colloidal, and above all dynamic particle systems?

Let us first clarify the concept using an analogy:

Imagine a floating raft composed of many small magnetic building blocks, with a group of people moving around on it. This raft has no fixed, rigid shape: the magnetic blocks attract one another, partially repel each other, and constantly rearrange themselves—these correspond to the lipids of the LNP. The people on the raft represent the modRNA. They are not passive passengers; they move, shift their weight, and thereby change the balance and shape of the raft. If more people move to one side, the raft deforms or becomes unstable. In the same way, modRNA influences the structure of the lipid particle. Conversely, the arrangement and strength of the magnetic blocks determine how easily or with how much difficulty the people can move—this corresponds to how the lipids influence protection, accessibility, and the behavior of the modRNA. Due to the constant movement of the water, comparable to Brownian motion, the entire system is in permanent flux and never reaches a true resting state.

The key point is this: there is no “container with contents” here, but rather a coupled system in which every movement of one part alters the whole.

Let us use a second analogy for those who think more acoustically, to make this more intuitively graspable:

Imagine a jazz band. The musicians (particles such as ALC-0315, the ionizable lipid, or DSPC, the synthetic phospholipid) each have individual strengths (e.g., ionizability). Together they produce music (the overall LNP system) that no soloist could generate alone. If the venue changes (the medium, e.g., pH value), the musicians adapt—a violinist becomes “louder” (ionized)—which alters the overall sound. At the same time, the sound dictates how each musician plays. It is an interplay in which the individual and the whole continuously adapt to each other without losing their core identity.

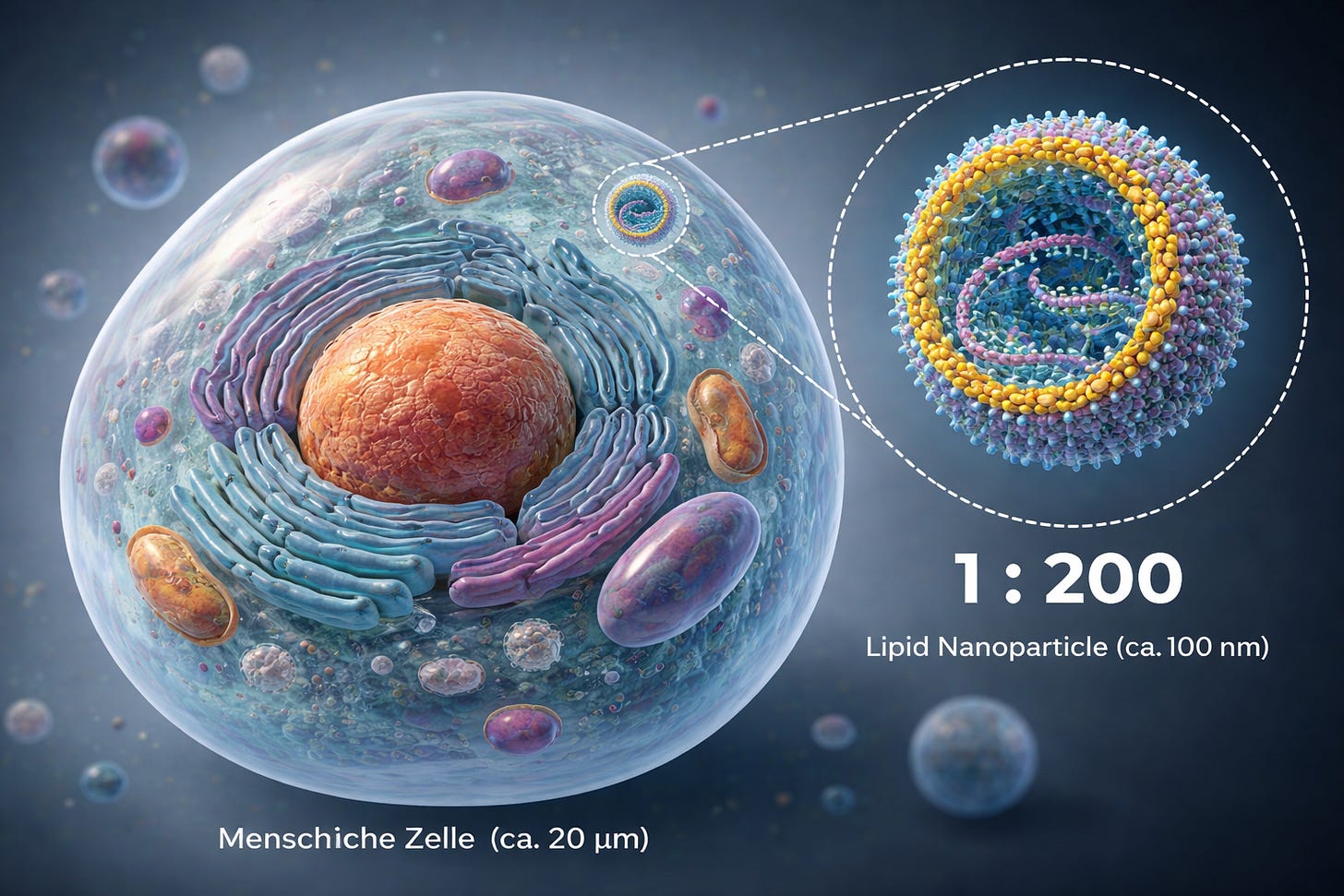

To get a sense of scale, let us briefly define NANO:

We are talking about liquid droplets that form a construct which, relative to the cell it enters and into which it releases its cargo—the modRNA—behaves, purely in terms of size differences, roughly like a soccer player on a soccer field.

This is, of course, only a rough analogy, as the system is even smaller; we are dealing with a ratio of approximately 1:100–200.

Now, to phrase this in a more scientifically demanding way—and you are welcome to ask your AI of “doom,” pardon me, of trust, about this:

A colloidal particle system describes an assembly composed of multiple individual components in which the individual physicochemical properties of the constituent particles (including the modRNA) mutually influence one another. Their mixing ratios determine the macroscopic behavior of the overall formulation in the initial medium, without allowing for a simple derivation of system properties from the properties of the individual particles, or vice versa—especially when the medium changes.

A central criterion of colloidal systems is their ability to undergo phase transitions. This condition is fulfilled by lipid nanoparticles: after cellular uptake, they undergo a pH-driven phase transition in which protonatable lipids change their charge and packing properties and transition from a structurally stable particle phase into a membrane-destabilizing, fusogenic phase. They are therefore dynamic, colloidal assemblies.

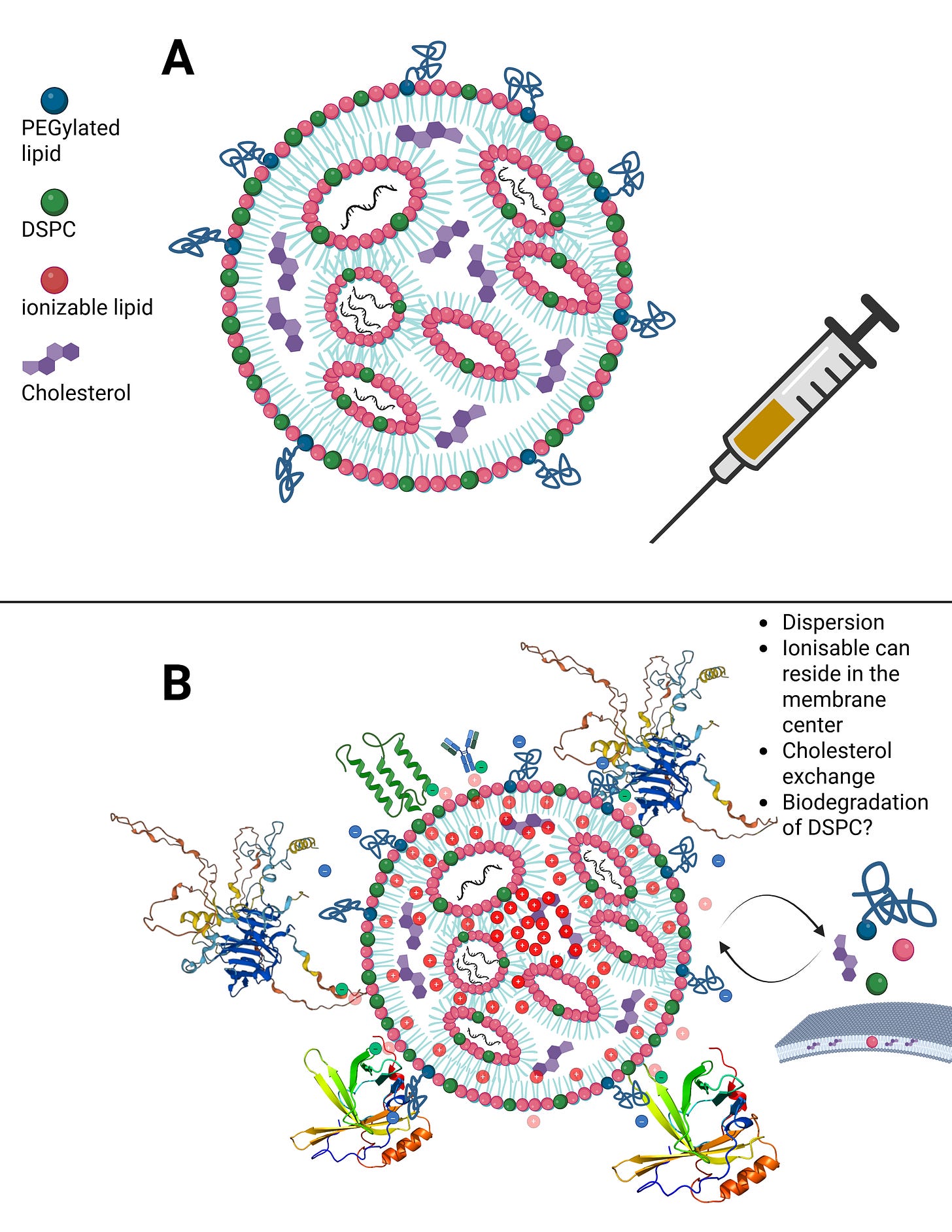

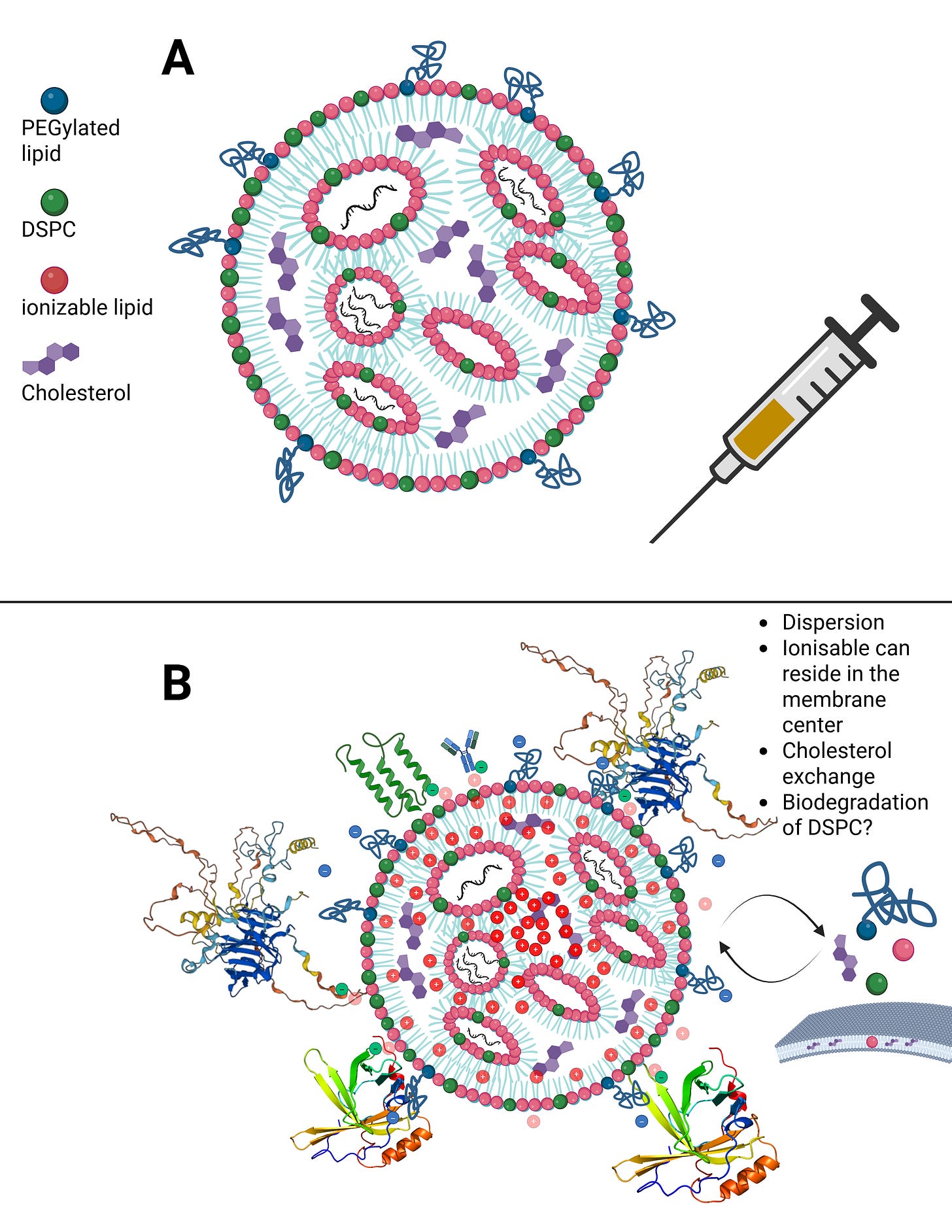

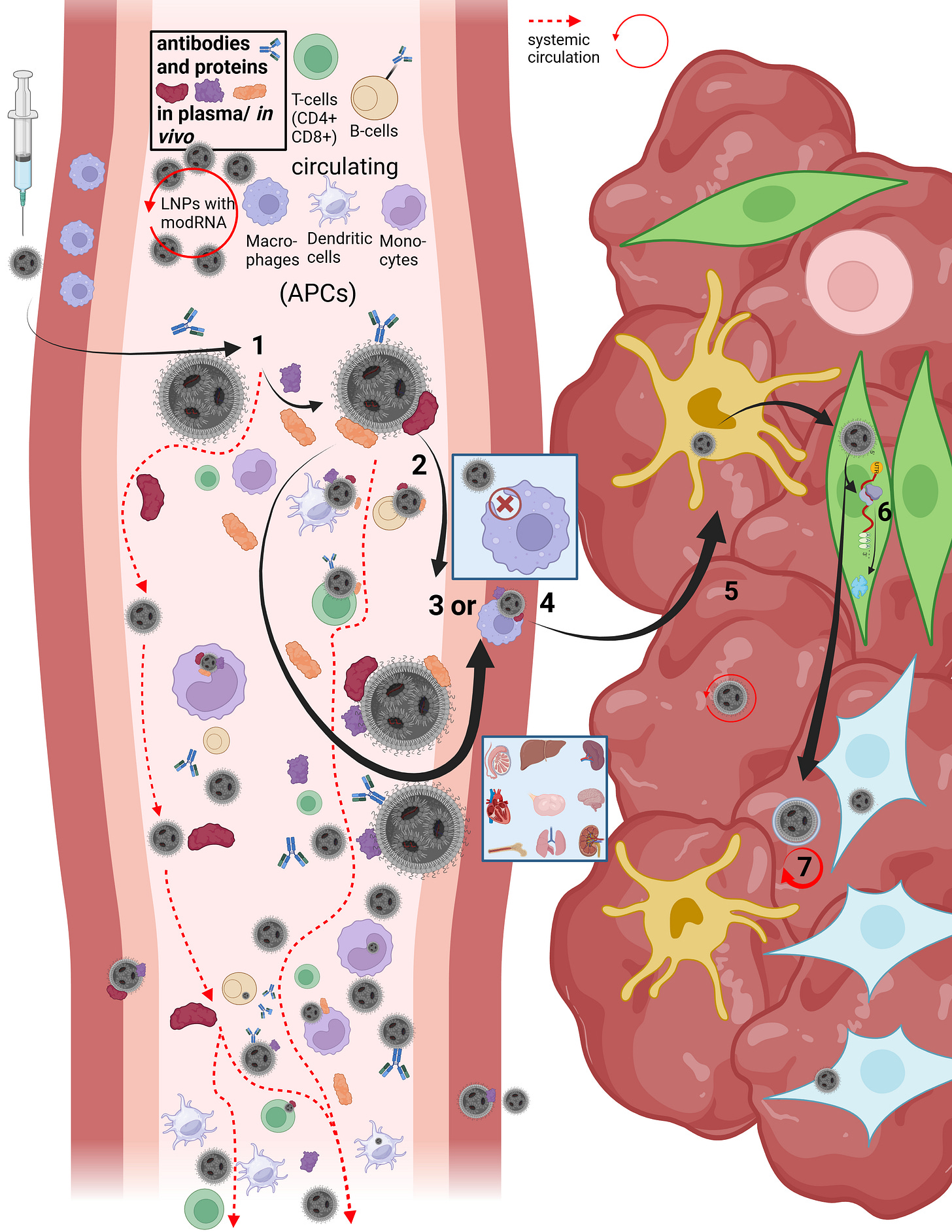

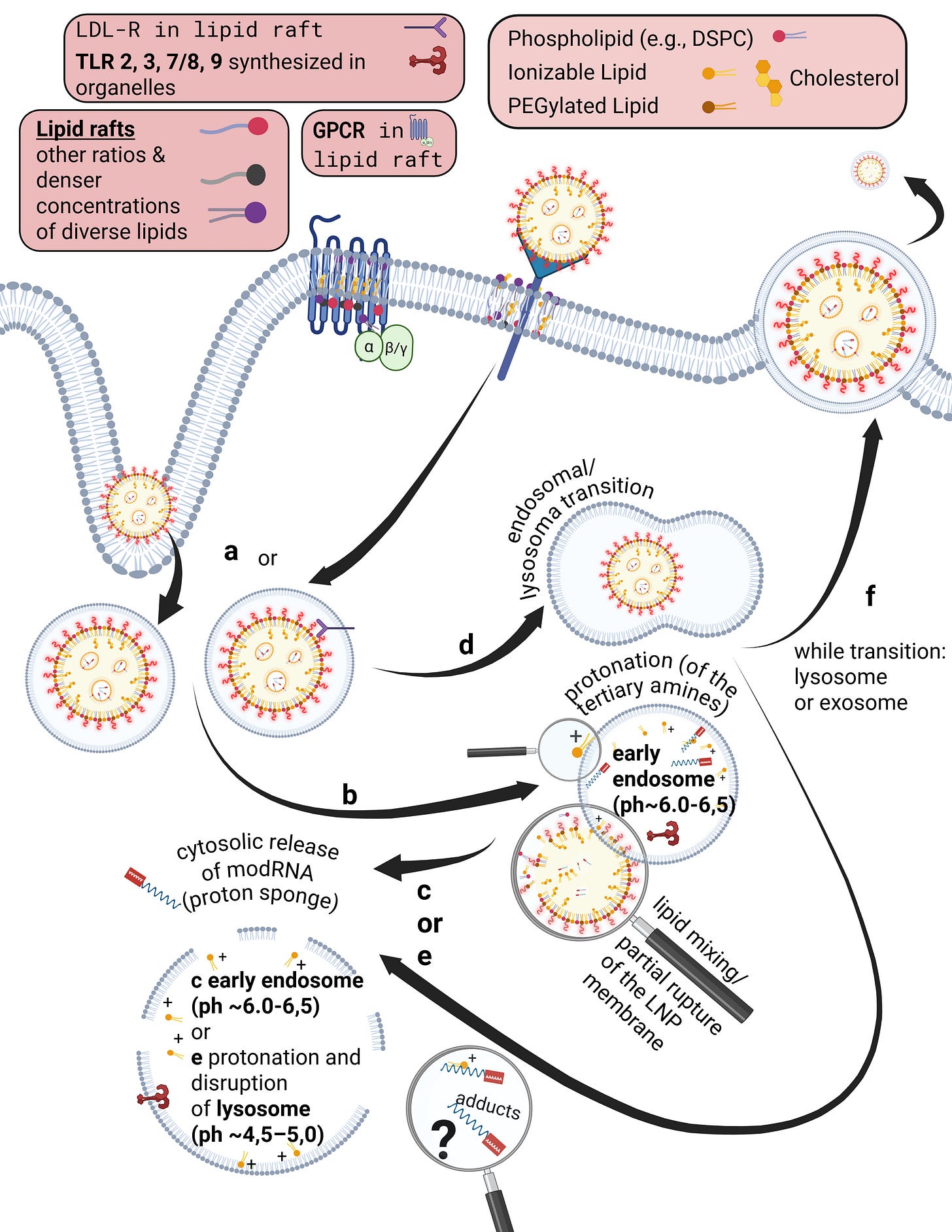

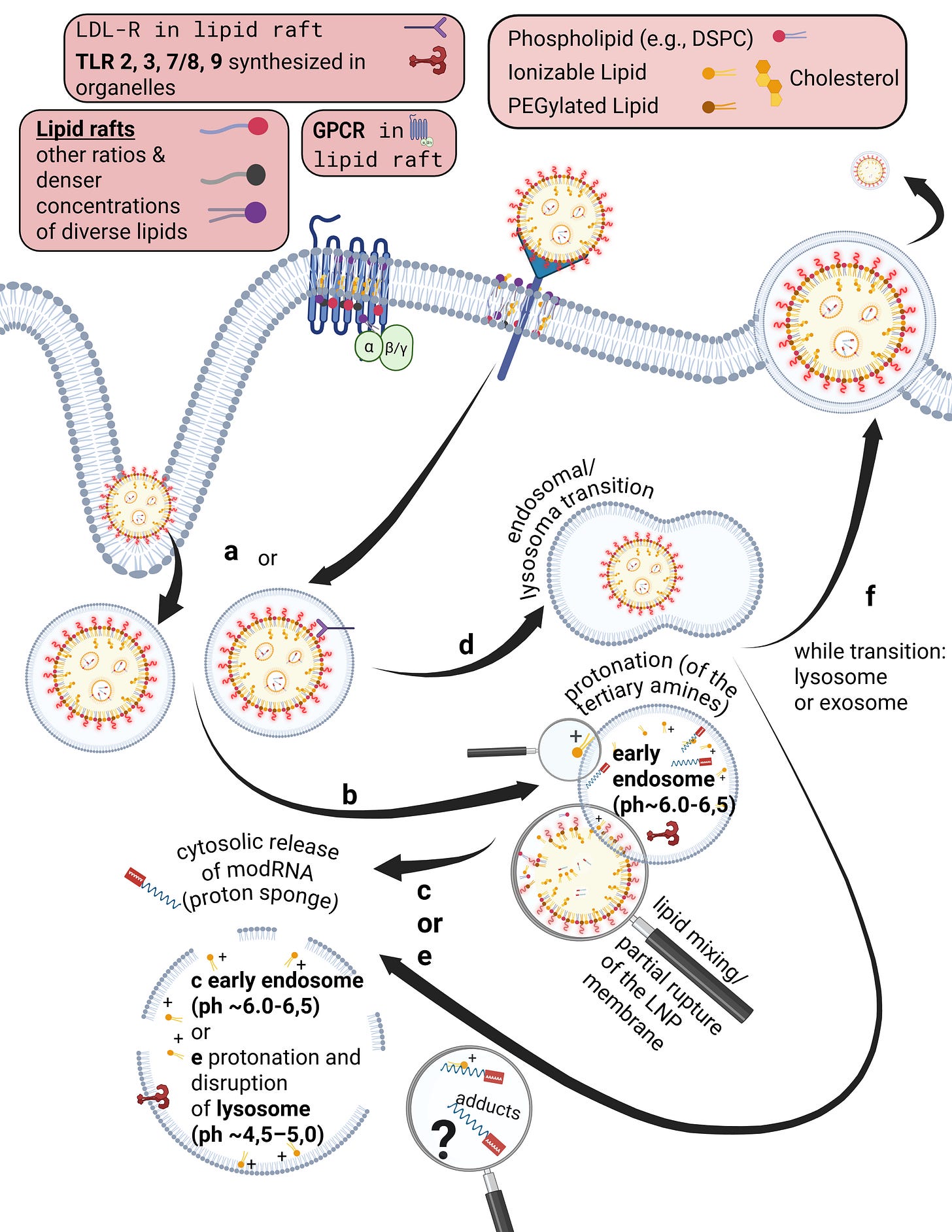

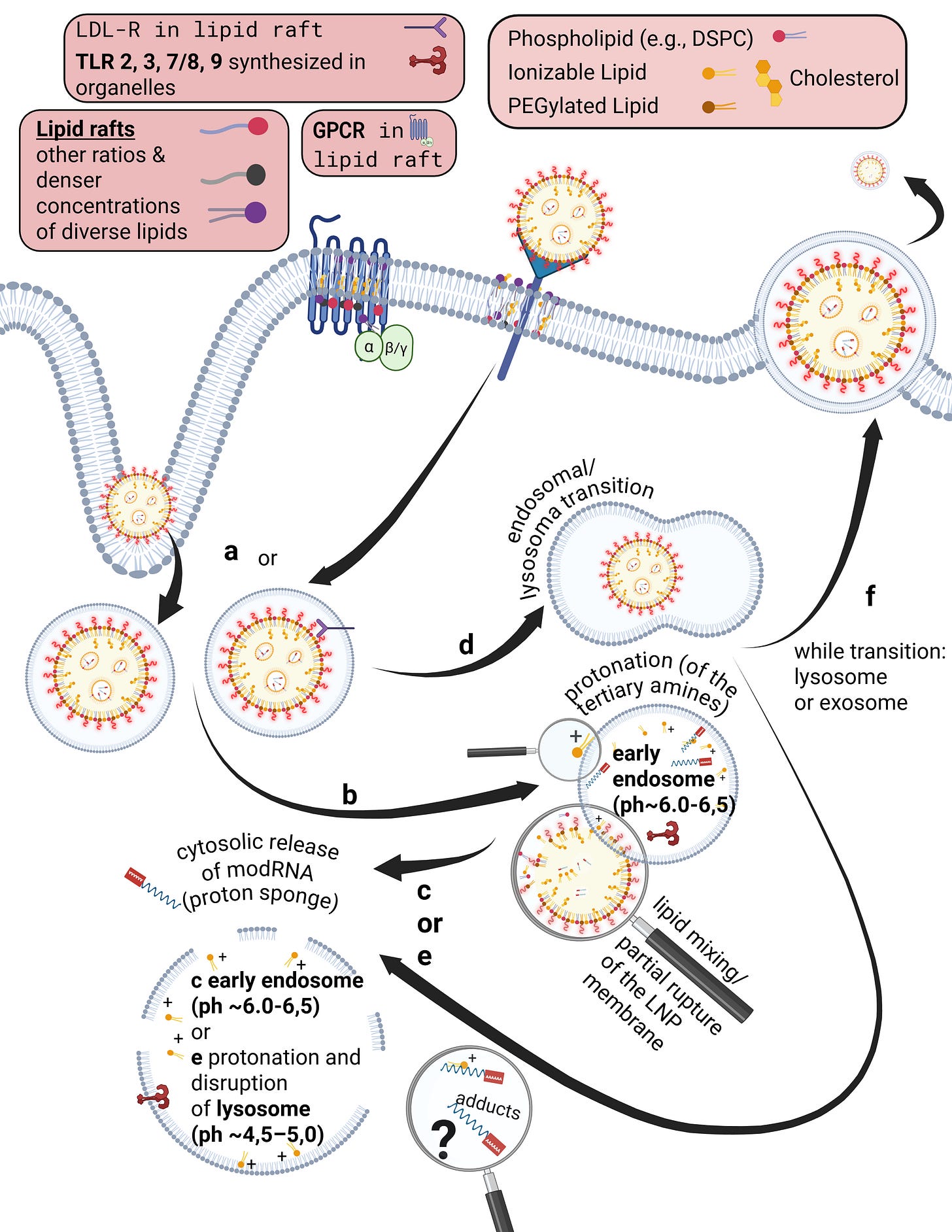

Let us now calmly revisit the slide that Maria Gutschi and I developed to better conceptualize the self-organizing principle of lipids in relation to the overall lipid nanoparticle.

In panel A, the schematic of a single lipid nanoparticle is shown. Four lipids form the outer layer and the interior of the lipid nanoparticle, depicted in different colors. Inside, individual rings are formed. The individual lipids bind and, through their differing physicochemical properties, form the overall particle containing the encapsulated modRNA. From this alone—and because physical interactions and forces are interacting here—it necessarily follows that a strongly negatively charged RNA must exert an influence on this particle. The modRNA is a so-called polyanionic polymer. Through its negative charge, it inevitably generates mechanical tension and thus an intrinsic organization of the lipid nanoparticle.

The formulations of the C-19 LNP-modRNA injections consist of an ionizable lipid containing a tertiary amine, the synthetic phospholipid DSPC, a PEGylated lipid, and cholesterol, which primarily resides in the inner interstitial spaces.

These four lipids, in specific stoichiometric ratios, form the complete particle. A single lipid nanoparticle contains between 30,000 and 60,000 ionizable lipid molecules. As demonstrated in countless publications, each of these lipids is in constant motion and behaves depending on the relative ratios of the lipid components to one another and on the encapsulated modRNA. It should therefore already be evident at this point that a simple mass-based model cannot be sufficient.

Traditional pharmacokinetics, however, relies on mass and particle number in its ADME framework (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion), assuming stable molecules that do not undergo structural changes when fundamental conditions change—that is, molecules that do not undergo phase transitions.

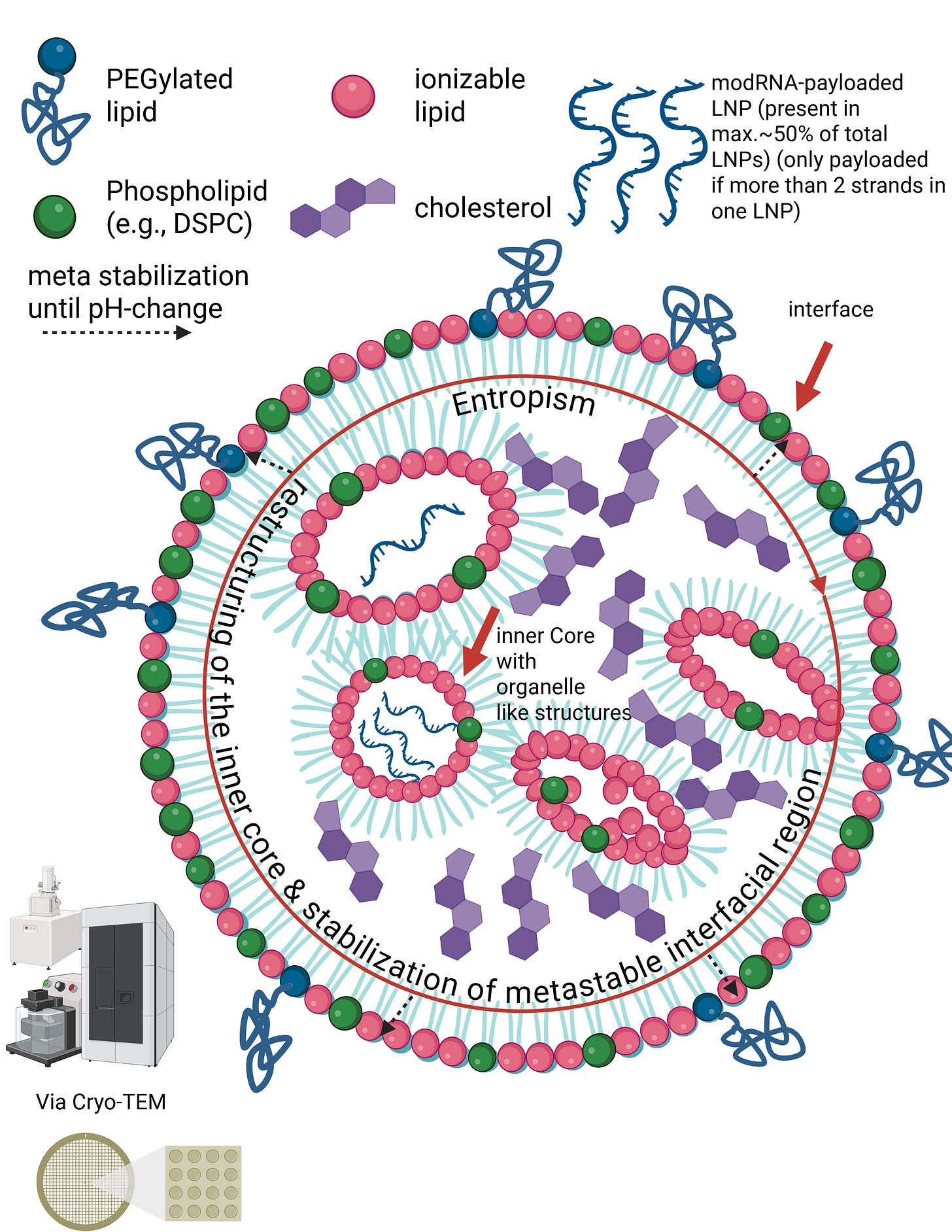

In Figure B, you can see what happens when an LNP transitions from a medium of pure alcohol, such as ethanol, into plasma or serum. Within minutes to at most one hour, dozens of endogenous proteins bind around the LNP, because it still emits a very slight outward charge. I will address uptake and distribution pathways, as well as this so-called protein corona, in more detail later.

This means that there is always a minimal scaffold on which further processes build. It is not the case that everything disintegrates completely and is then reassembled from scratch. For example, Liu et al., and in particular Liau et al., demonstrated using scanning electrochemical microscopy that the PEGylated lipid detaches first, followed by the ionizable lipid, and finally DSPC, leaving only cholesterol and the modRNA behind. In addition, cholesterol exchange occurs during LNP uptake. More on this later.

In summary, nanoparticles do not permit traditional drug analysis because they restructure themselves upon changes in the surrounding medium. However, applying a traditional pharmacological model based on mass requires that the original structural ratios remain constant.

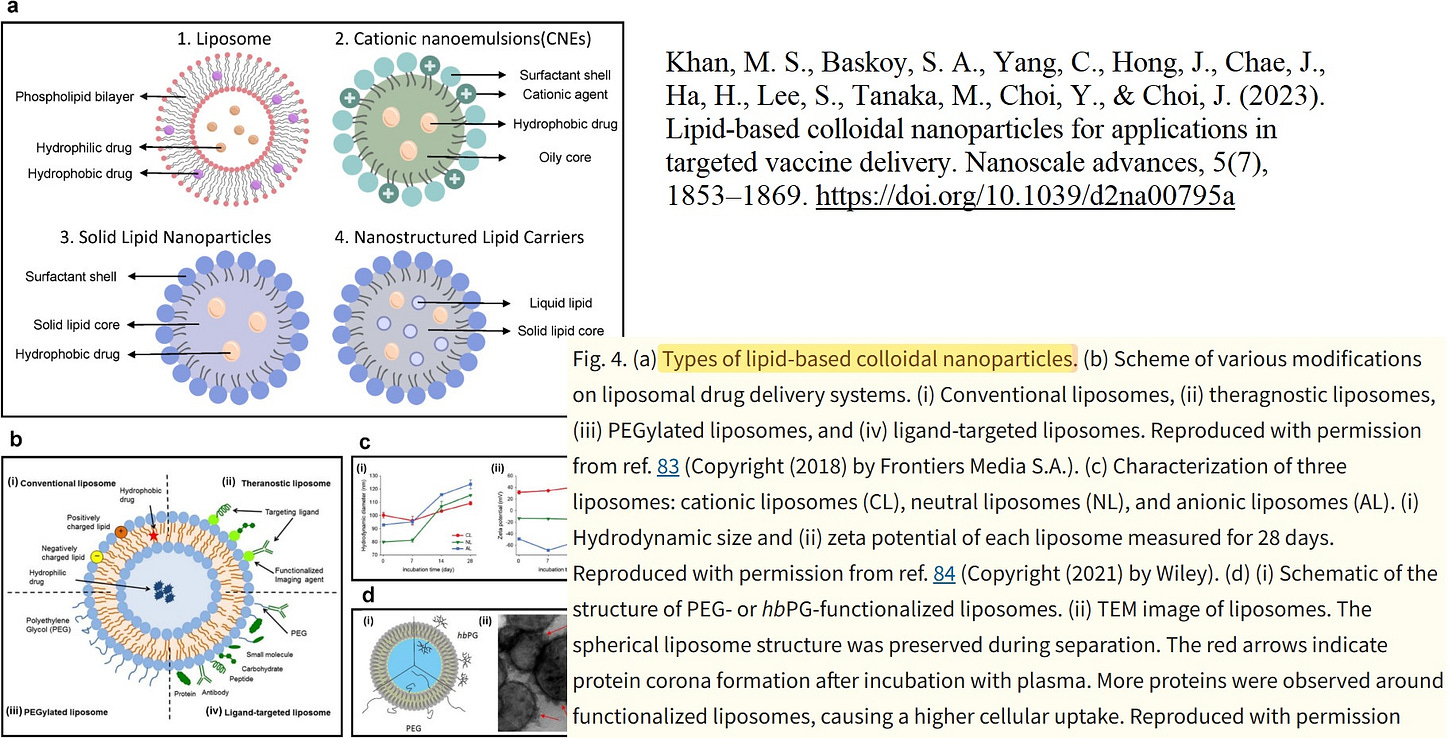

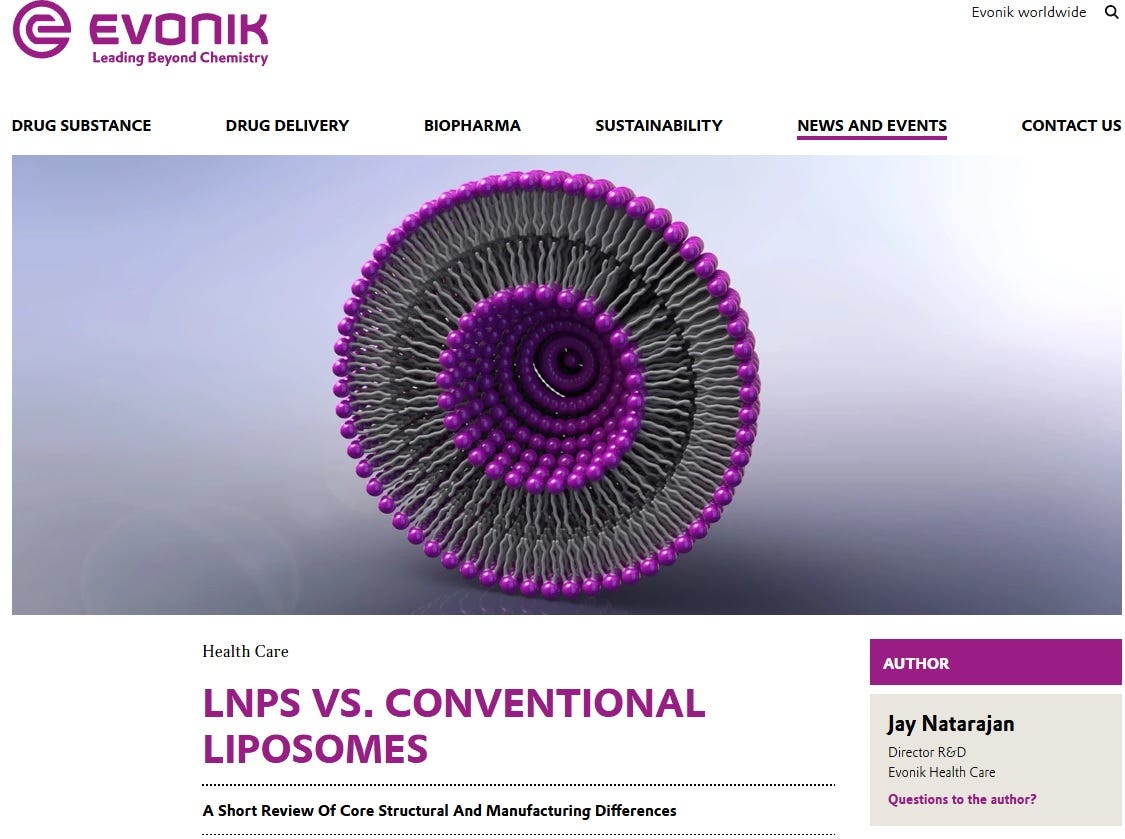

After having examined the fundamental physicochemical properties of lipid nanoparticles as used by Pfizer and Moderna in the COVID-19 injections, the distinction between lipid nanoparticles and conventional liposomes must now be briefly clarified.

In one of his recent discussions with Dr. Wodarg, Dr. Kremer claimed that liposomes or even micelles can be equated with lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). This equivalence, however, is not tenable. Even though I already addressed this during the discussion, I would like to explicitly reiterate it here.

Let us first clarify why micelles can be excluded.

A micelle is a small, self-organized structure formed by amphiphilic molecules (e.g., surfactants) in an aqueous solution. Amphiphilic means that a molecule contains both hydrophilic and lipophilic components. This description does not apply to lipid nanoparticles for three fundamental reasons:

LNPs do not possess a simple hydrophobic core.

LNPs consist of multiple different classes of lipids, not a single uniform amphiphilic molecule type.

The lipids in LNPs are not arranged radially, as is typical for micelles. By radial arrangement, we mean that molecules are ordered from the center outward, which is characteristic of micelles but not of LNPs.

Next, let us clarify the difference between LNPs and liposomes. I quote Jay Natarajan from Evonik, an official manufacturer of LNPs:

“Liposomes have an entrapped aqueous volume, while LNPs do not. Instead, LNPs contain the lipid in the core of the particle, along with nucleic acids such as RNA or DNA. While LNPs can take a variety of forms, if you were to look closely at their most common structure, you would see a multi-layered core of contracted rings of lipids and nucleic acids, interspersed between lipid layers.”

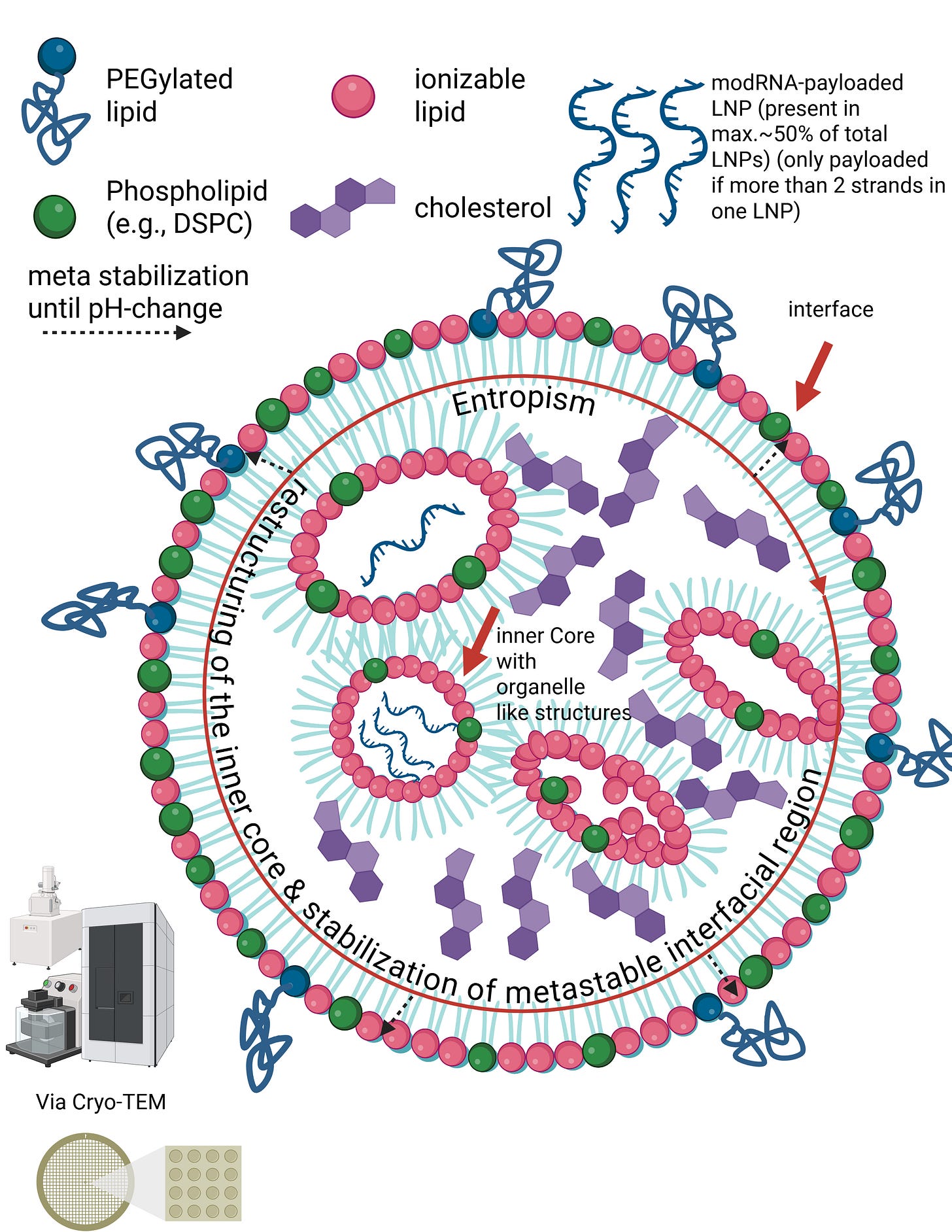

I will now try to explain this in an accessible way and then summarize it precisely once more.

Liposomes are nanoparticles with an aqueous interior surrounded by a clearly defined lipid membrane. Lipid nanoparticles function differently. In the slide, you can see the structural principle of an LNP as visualized, for example, by cryo-transmission electron microscopy. LNPs have neither a hollow interior nor stable internal membrane layers. Instead, the RNA inside LNPs is directly bound to specific lipids. These lipids and the RNA attract one another due to their electrical charges and jointly form a compact, disordered core. This core is not a rigid structural component, but a dynamic assembly held together only by many weak, non-covalent forces. The outer lipid shell of an LNP is therefore not mechanically supported by inner layers, but rather arises through lipid self-organization. The entire particle is sufficiently stable for transport, yet deliberately metastable so that it can reorganize upon contact with cellular membranes and release the RNA after internalization.

In other words, the internal region of LNPs does not form classical structural layers in the sense of lipid bilayers. Instead, the modRNA is embedded in an amorphous, dynamic core of ionizable lipids, stabilized by an interplay of electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic effects, counter-ion binding, and entropic forces. The outer lipid layers are therefore not mechanically supported by internal “layers,” but represent an autonomous, metastable interfacial phase.

From this it follows that we must abandon the classical terminology of conventional pharmacology and that a paradigm shift in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is required.

This raises the question: why would one deliberately construct such an extraordinarily complex nanoscale structure, if it should by now be clear from my presentation that the consequences are only very limitedly predictable, because non-linear behaviors are to be expected at the latest after injection of a colloidal multi-particle system?

The original idea behind modRNA-LNP technology was to smuggle something into cells—for example, the blueprint for spike proteins. RNA, in this case modRNA, is strongly negatively charged and is therefore electrostatically repelled by the likewise negatively charged cell membrane. It is enzymatically unstable in the body and, without a carrier system, can trigger pronounced immune reactions. For these reasons, it cannot be used in vivo—that is, in a living organism—without a suitable transport vehicle. Thus, a carrier was required.

It quickly became clear that permanently cationic or anionic liposomes are associated in vivo with relevant toxicity and nonspecific membrane interactions due to their constant charge. Moreover, research had already been underway for some time on more complex transport strategies, with the goal of making them less toxic.

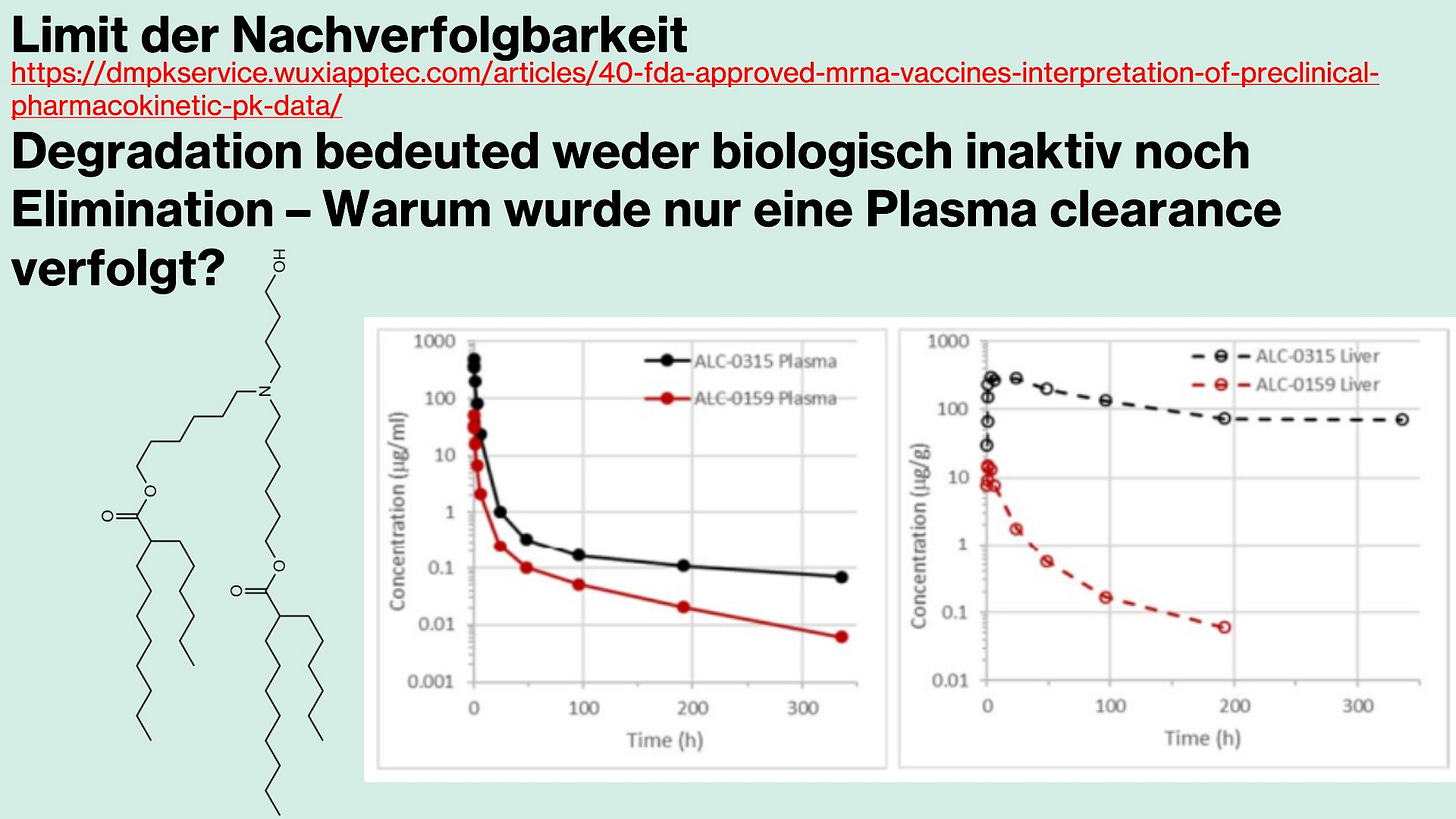

This was believed to have been achieved with ionizable LNPs: here, the charge is not fixed but depends on pH—that is, on the acidic, neutral, or basic milieu in the blood and within the cell. I will elaborate on this further when we arrive at the uptake mechanisms of LNPs. It is precisely this complexity, as outlined so far, that makes predictions about long-term behavior or biodistribution so difficult, because the current state of the art allows only limited in vivo tracking capabilities, and tracking signals are lost very quickly. The major misinterpretation accordingly lay in viewing LNPs primarily as controllable transport vehicles, rather than recognizing them as biologically active entities whose behavior extends far beyond simple charge relationships.

Even though this has been highly technical up to this point, it is essential to understand these fundamental properties in order to even begin to comprehend what actually happens in vivo—that is, how LNPs distribute after injection and are taken up by cells. These processes are what we refer to as pharmacokinetic properties.

*Figure is actualized and not original from V1 of Maria and my preprint (we will add a v2 if we find free minute)

What actually happens after injection? The devil is in the details.

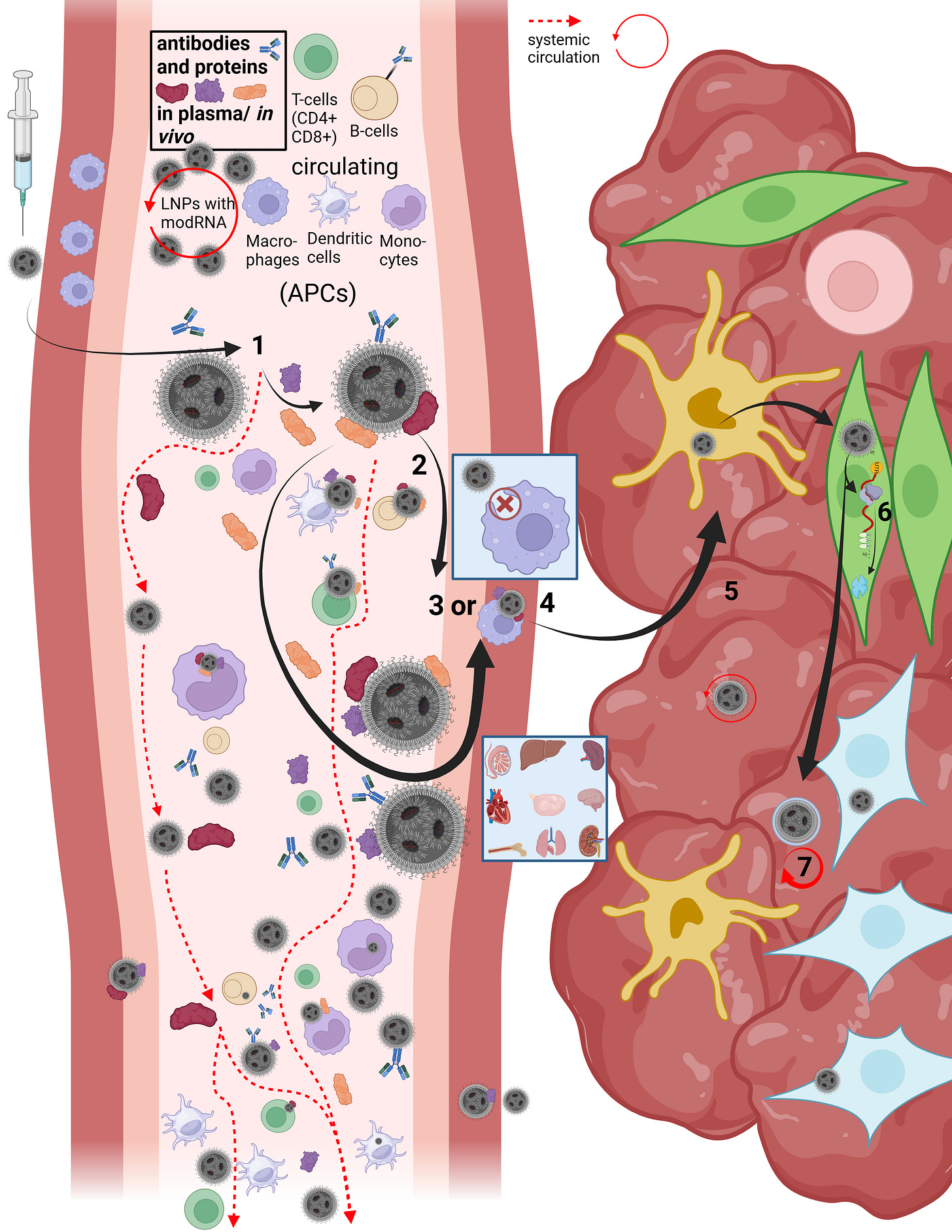

On this slide, Maria and I reconstructed the in vivo “journey” of LNPs in our first paper.

LNPs have multiple uptake pathways through which they can reach various organs via different mechanisms. While the route is influenced by the mode of administration—i.e., whether injected intravenously or intramuscularly—it is not fully determined by it. Once LNPs enter the organism, their physicochemical properties are too randomized to allow precise prediction of their exact trajectory. As shown earlier in the structural slide, Figure B, a wide variety of endogenous proteins bind to LNPs as soon as they enter the system and undergo their first medium transition. This leads to the formation of the so-called protein corona. The formation of the protein corona occurs via different mechanisms that are not yet fully understood. However, it can be assumed that already at this stage—with billions of lipid nanoparticles containing trillions of individual lipids—the first biological effects on proteostasis may arise, meaning initial disturbances in protein homeostasis are possible.

Let us now briefly trace the cellular uptake pathways to better understand the journey of an LNP. First, we consider what must happen at all for a cell to release modRNA, without yet going into the precise release mechanisms—I will return to those later.

After injection, several research groups made remarkable observations: a fraction of the LNPs enters the bloodstream directly via diffusion, meaning slow percolation through muscle tissue. The majority of LNPs initially remains in the muscle, where they attract immune cells, in particular migrating T cells and, above all, dendritic cells.

In addition, a smaller fraction can reach muscle-resident macrophages and be taken up via alternative uptake pathways, although this occurs rarely and nonspecifically. In this context, transfection refers to an uptake process that is not comparable to the originally intended uptake mechanisms. In this presentation, we focus primarily on dendritic cells, as these are described in the literature as the immune cell type most frequently transfected by LNPs. Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells and migrate to lymph nodes after encountering a pathogen.

When LNPs first come into contact with immune cells, they migrate extremely rapidly into the draining lymphatics. From there, they can enter the bloodstream and distribute systemically. Due to the formation of the protein corona—which gives each individual LNP a quasi-individual identity—it is not predictable which cell types will take up how many LNPs. For example, it has been shown that LNPs can bind to lipid transporters such as apoproteins, as well as to vitronectin and ficolin-1—both proteins involved in blood coagulation and cardiac function. The complete set of interaction partners of the LNP protein corona in vivo in humans has not yet been fully characterized.

However, the exact mechanism by which LNPs enter the systemic circulation is still not fully understood. Based on an extensive review of the literature, we assume that several mechanisms can occur simultaneously. On the one hand, LNPs may transfect immune cells directly, which then transport them into the lymph. On the other hand, LNPs may initially bind only to cell surfaces without being internalized.

This is where the importance of the metastable nature of LNPs becomes evident: regardless of the transport mechanism—whether diffusion, cellular uptake, or binding to immune cells—physical shear forces and interactions with the surrounding environment alter the structure of the LNP. PEGylated lipids can be shed, individual lipids can exchange with cellular membranes, and these processes alone can already trigger significant reactions, such as complement activation–related pseudoallergy (CARPA). These dynamics make it very difficult to precisely identify LNPs for longer than a few hours to days.

Once an LNP enters the circulation, several scenarios are possible. It may directly transfect circulating immune cells. Importantly, if an LNP encounters, for example, a circulating monocyte—a cell that is already phagocytically active—it is not classically phagocytosed and degraded in lysosomes. Instead, uptake occurs via alternative pathways that, according to our hypothesis, may already lead to functional impairment of the cell. These cells can subsequently migrate into other tissues. Moreover, monocytes are precursor cells: depending on the signals they receive and the environment they encounter, they can differentiate into other cell types such as macrophages or dendritic cells.

However, LNP uptake is not limited exclusively to immune cells. It is evident that various types of endothelial and epithelial cells, as well as many other cell types, can also be transfected. This becomes particularly relevant when we consider how modRNA enters the cell and is subsequently released for translation.

Now that we better understand how LNPs can enter the circulation at all, it becomes clear that the restructuring and individualization of each single particle necessarily affects uptake pathways across different cell types. The frequently used statement that “LNPs distribute throughout the entire body” therefore falls short, as it neither describes how this occurs nor what happens afterward. We now turn to steps 3 through 7.

Depending on the protein corona formed and the specific LNP entity, it is determined how LNPs can penetrate individual tissues and how they subsequently act there. LNPs can enter organs either through fenestration—that is, passage through tissue gaps—or via transcytosis. Transcytosis describes a process in which an LNP is first taken up by a cell and then released again in extracellular vesicles, so-called exosomes, in order to enter the tissue. During this process as well, the LNP restructures itself or integrates parts of its lipids into the vesicle membrane. This results in so-called lipid mixing, meaning that lipid components of the endosome exchange with those of the LNP. While this may sound complex at this stage, it will become clearer later when we examine cellular uptake and modRNA release in more detail.

If an LNP—or an LNP contained within a vesicle—reaches the tissue of an organ, it can continue to circulate locally and transfect a wide variety of cell types. These include, among others, organ-resident macrophages such as Kupffer cells in the liver. At this point, it is determined whether the modRNA is released for translation or not. In 85–97% of cases, no translation of the modRNA occurs. Only a small fraction of internalized LNPs actually leads to protein production, which relativizes the efficiency of the process. The remaining modRNA-loaded LNPs can therefore re-enter the circulation.

As discussed, the final fate of an LNP has not yet been conclusively clarified, as long-term observation of this process has so far been only possible to a limited extent.

In addition, it should be considered that the injection technique itself—for example, not aspirating prior to injection—could theoretically influence very rare, immediate adverse reactions. However, this hypothesis has not been systematically investigated and remains speculative for the time being.

Before we turn to what will at first glance probably appear to be a very complex slide, I would like to briefly summarize the key points I have explained so far in this lecture from a physicochemical and pharmacodynamic perspective.

The most important points for understanding how chaotic and unpredictable lipid nanoparticles are, distilled from the considerations so far, are the following:

LNPs restructure their overall form—and thus their overall properties—by exchanging individual lipids or by losing them, for example due to shear forces. They are only metastable and bind seemingly randomly to endogenous proteins almost immediately. As of the time of this lecture, this process is still not sufficiently understood. The resulting protein corona gives rise to numerous uptake pathways into individual organs and from there further into cells, where—according to the manufacturers, ideally—the LNPs release their genetic payload and interact with the cell. However, only a very small fraction actually releases this payload. The remainder re-enters organ and blood circulation until it is taken up again. Accumulation—that is, the final concentration of LNPs in organs—occurs primarily in the liver, kidneys, and spleen. These circumstances make it extremely difficult to track LNPs over longer periods of time. It is significantly easier to label the genetic material in vivo. However, this does not tell us where the LNPs themselves migrate. This point is crucial for the next slide, where we turn our attention to the cell membrane and uptake pathways.

In summary, due to their poor traceability in vivo and their non-computable nature, LNPs could be described as “ghost particles.” We lose tracking signals at the latest after the second remodeling step—that is, after uptake and subsequent exocytosis or re-release into the circulation. Furthermore, LNPs should be understood as a new class of medicinal products, most aptly described as metastable supramolecular assemblies.

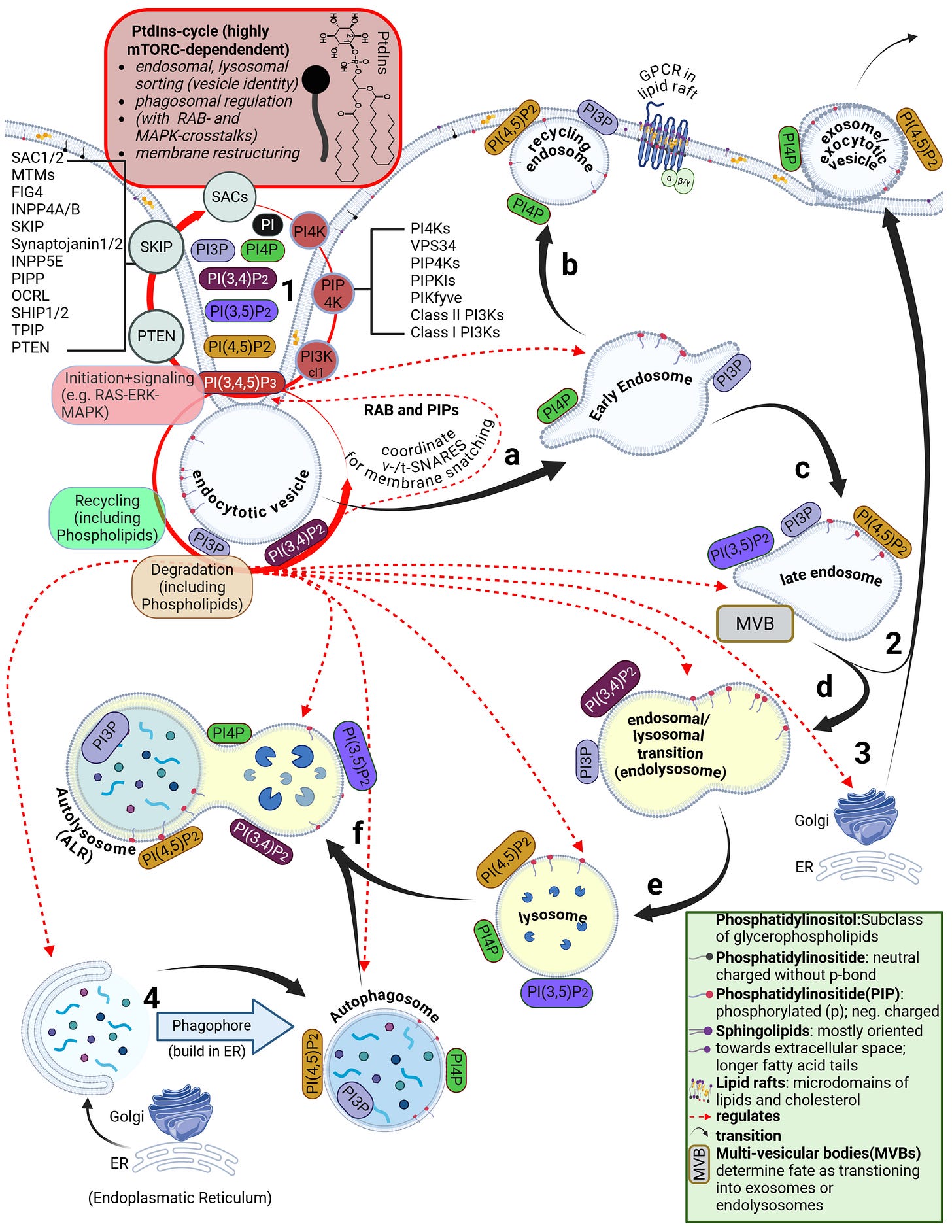

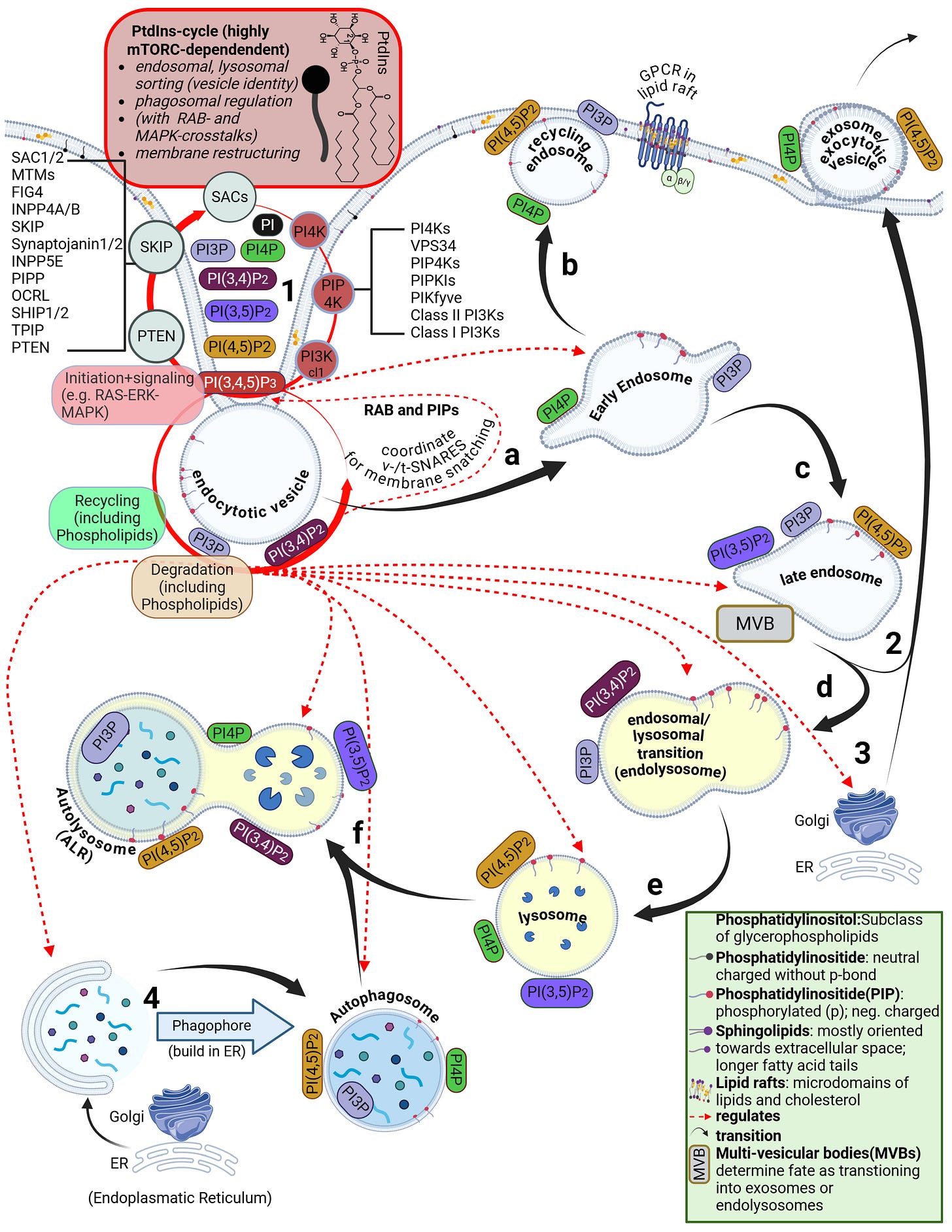

Having recalled the physicochemical and pharmacodynamic properties once more, we now turn to the uptake mechanisms. To do so, we must first clarify the concepts of the cell membrane—which consists of a phospholipid, fluid bilayer—and of the endosome and lysosome.

The lipid bilayer is the actual starting point at which the previously discussed physicochemical and biophysical properties of LNPs become effective—and where the real biological consequences of forcibly overcoming this barrier begin.

The bilayer consists of individual lipids whose head groups are oriented both outward, toward the extracellular side, and inward, toward the cytosolic side. Due to its water-repellent and lipid-binding nature,

this structure separates the cell from the surrounding tissue and body fluids and renders it initially impermeable unless specific conditions are met. The membrane is composed of various phospholipids as well as cholesterol, which preferentially inserts into the hydrophobic core of the membrane, between the diametrically opposed fatty acid chains of the phospholipids. There, cholesterol serves a primarily stabilizing and ordering function. This region is characterized by an energetic equilibrium with only minor dynamic fluctuations, which—provided no external perturbations act—ensures high structural stability of the membrane.

However, the lipid bilayer is not homogeneous. In addition to phospholipids and cholesterol, other lipid classes are present, such as sphingolipids and glycolipids. The arguably most important class—despite its low abundance and still only partially understood nature—are the phosphatidylinositides. These are predominantly oriented toward the cytosolic side of the membrane. Their binding properties and their phase-transition products determine the entire intracellular uptake machinery. This includes endocytosis, the behavior of endosomes, and the parallel signal transduction from receptors to their respective intracellular targets.

Phosphatidylinositides are particularly enriched in so-called microdomains of the cell membrane, where the composition, concentration, and density of lipid classes differ markedly from the surrounding membrane. These microdomains are referred to as lipid rafts. Depending on the study and cell type, they account for approximately three to five percent of the total membrane area. Numerous receptors responsible for specific binding of bioavailable substances—such as hormones—are located within these lipid rafts. In addition, there are also various ion channels

that can allow individual ions to pass through. Bioavailability here means that a substance possesses specific ligands, i.e., binding sites, that match corresponding cellular receptors.

Some receptors are co-internalized, meaning the entire receptor–ligand complex is taken up into a vesicle. Other receptors, by contrast, merely bind the ligand and undergo a conformational change. This conformational change triggers specific intracellular processes. As illustrated on the slide, G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), for example, bind a wide range of ligands such as photons (so-called opsins), ions, vitamins, proteins, and many others. They are not primarily internalized but instead transmit information into the cell upon ligand binding.

The biological problem with LNPs:

Both receptor-specific and receptor-independent uptake are, in strict scientific terms as already mentioned, referred to as transfection. Although many studies define transfection as the entire process up to the release of modRNA into the cytosol, these processes should be strictly separated, as each has independent biological consequences and together they can produce both synergistic and antagonistic—that is, mutually amplifying and/or attenuating—effects.

Already during the crossing of the cell membrane, individual lipids from the LNP mix with and exchange into the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. From a strictly energetic perspective, it is also plausible that individual ionizable lipids can reside within the hydrophobic core of the bilayer—that is, remain there. It is biologically implausible that they could even be partially degraded in this location. Furthermore, upon contact with cells, LNPs actively promote uptake and enter the endosome.

Endosomes are vesicles with a single lipid membrane that enclose the LNP after uptake. They are directly budded off from the cell membrane. This uptake process generally applies to larger molecules, particles, aggregates, nanoparticles, as well as to smaller ligands.

However, there are important differences. The uptake process—endocytosis—can occur for LNPs, depending on the protein corona formed, either with or without receptor binding, for example via clathrin-mediated endocytosis or via internalization through low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLRs). Clathrin is a coat protein involved in the formation of transport vesicles at the plasma membrane during receptor-mediated endocytosis. You do not need to understand the individual receptors and uptake pathways in detail here—only the underlying principle: this is a biologically nonspecific process that contradicts any natural form of substance uptake, since even viral particles are co-evolutionarily bound to specific host cell factors. Because lipid exchanges already occur at this stage, as discussed earlier, it is biologically plausible to assume that receptor alterations may occur—both in functionality and in localization.

Furthermore, during the transition from the early to the mature endosome—determined in part by the specific lipid composition of the endosomal membrane—the subsequent fate of the endosome is decided. It is determined whether it enters the endosomal–lysosomal maturation pathway or is returned to the cell membrane as a recycling endosome.

This process depends strongly on specific phosphatidylinositides. In the case of recycling, endosomal membrane components are sorted, redistributed, and reintegrated into the cell membrane, allowing lipids of the endosomal membrane to be reused for membrane reconstruction.

The lysosome, by contrast, is an intracellular vesicle that develops from—or matures out of—the endosome and contains various enzymes that digest toxins and separate useful from unusable material.

The ionizable lipids used in currently deployed modRNA–LNP platforms are tertiary amines. These tertiary amines—specifically ALC-0315 and SM-102—have an acid dissociation constant (pKa) in the range of approximately 6.2 to 6.8. In a neutral milieu, they are therefore predominantly uncharged, as the overall particle—the lipid nanoparticle itself—is nearly electrically neutral at physiological pH. In addition, the PEGylated lipids are intended to shield against premature charge changes. The pH value represents the negative decadic logarithm of the proton concentration and is thus directly relevant for acid–base reactions. In simpler terms, pH determines the rate and extent of proton uptake.

When the pH falls below the pKa, these ionizable lipids become protonated. This occurs only within the endosomal compartment, where the pH decreases during maturation to approximately 4.5–5.0, at least according to classical assumptions and earlier observations. Under these conditions, protons from the acidic milieu bind to the ionizable lipids, leading to a reorganization of the lipid nanoparticle. The relationship between the lipid pKa and the local pH is decisive for the subsequent intracellular course.

Through protonation, LNPs destabilize the endosomal membrane by disrupting its structural integrity and promoting the formation of unstable, transient pores. As a result of this partial membrane destabilization—which ultimately leads to rupture of the endosomal membrane—the modRNA can escape from the LNP and the endosome into the cytosol of the cell. By rupture, we mean holes in the membrane, which inevitably trigger inflammatory processes. This process is referred to as endosomal escape. It is not a passive diffusion process, as would be typical for many substances enclosed in endosomes, but an actively driven process mediated by physicochemical membrane interactions. In diffusion, substances would slowly passively leak through the membrane based on specific biochemical properties.

Interestingly, more recent studies show that endosomal escape preferentially occurs in the early endosome and is strongly time-dependent, suggesting that it is not the maximally acidic environment of late endosomes or lysosomes that is decisive, but rather a narrowly defined time and pH window. This explains why modRNA release is so inefficient. Current studies estimate that only about 3–15 percent of modRNA is translated into protein at all. These uptake and release processes disrupt overall cellular homeostasis—that is, the cell’s internal balance. In particular, endosomal disruption triggers highly inflammatory processes.

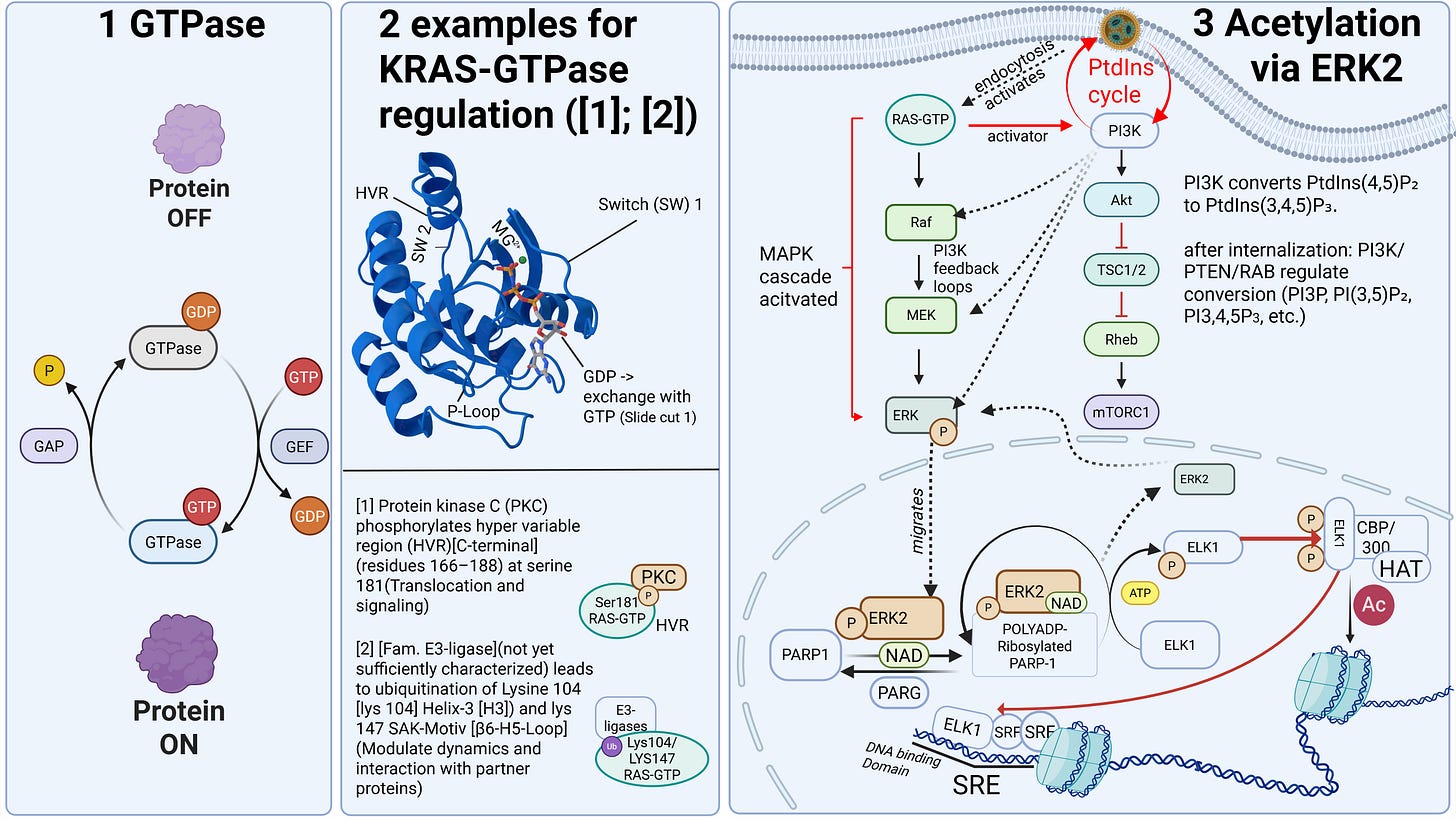

In addition, cellular communication is impaired, something we know at the latest from liposome research. In my example slide, a signaling pathway is shown that begins at the cell surface and extends to chromatin regulation—that is, epigenetic control of DNA. The signal proceeds as a cascade toward the nucleus, where it can activate or alter regulatory programs. A cascade in this context refers to a usually self-amplifying chain reaction that, once initiated, can only be regulated to a limited extent.

As cellular communication would exceed the scope of this lecture, I will only note here that our understanding of it remains very incomplete. For those who wish to explore this in greater depth, we discuss the most plausible signaling pathways in our work with Dr. Stephanie Seneff. Signaling pathways operate in nonlinear probability regimes that are strongly dependent on input signal strength and therefore evade simple cause-and-effect models. Everything begins at the cell membrane, as it directly interacts with receptors and ensures their functionality.

Disruptions in communication within a single cell can lead to systemic effects in neighboring and even distant cells, for example through the release of hormones, growth factors, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and numerous other extracellular signaling pathways. In addition, it is reasonable to assume that the process of transfection and endosomal escape places a heavy burden on the cell’s energy budget, making it plausible that the transfected cell may enter senescent states—that is, switch to minimal operation and focus solely on self-preservation. This may, for example, be promoted by increased secretion of interleukin-6, which has been demonstrated multiple times in vivo.

Additionally, another possible and already partially documented phenomenon is the epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes, resulting in reduced immune surveillance. This means that their overall functionality is fundamentally altered by specific processes.

Furthermore, as repeatedly confirmed in vivo, there is overexpression of specific monocyte ligands, namely programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1), which further favors the scenario described here. Epithelial cells can become stressed and senescent, thereby influencing neighboring cells, while those neighboring cells may nevertheless remain proliferative. This means they can continue to divide despite being in a stressed environment, which increases the likelihood of malignant transformation.

Under such conditions, control of transformed cells is severely impaired—a scenario that could systemically promote the development of metastases, as both immune surveillance and cellular homeostasis are profoundly disrupted.

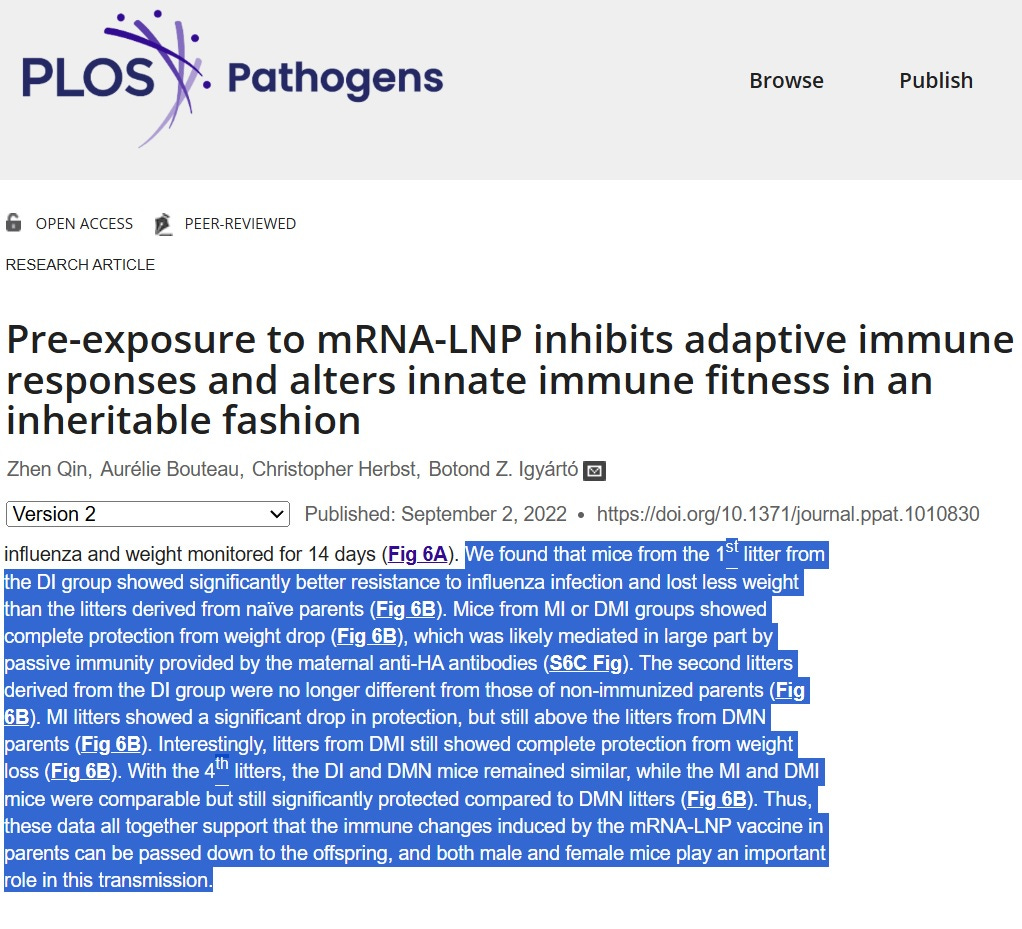

In an extensive mouse experiment by Qin et al., it was shown that even mere exposure—that is, contact with empty LNPs as currently used—led to markedly altered immune responses to viral and bacterial pathogens in the mice. Furthermore, the experiment demonstrated that this effect was transmitted to the next mouse generation, as would be expected if profound epigenetic changes were involved.

Biodegradation

Biodegradation describes the breakdown of a drug’s molecules and their intermediate products until complete termination—that is, how a product is degraded and how many phases are involved.

There is not much to say about the biodegradation of the individual lipids, not because there is little to say, but because these processes are poorly understood. Very few studies have been conducted, and current knowledge of the precise degradation pathways remains largely speculative.

It is clear that certain enzymes—so-called -ases—must cleave the fatty acid tails of the lipids. However, particularly with ionizable lipids, there are acute problems, and these processes are more than inadequately characterized. It is known that the ionizable head groups, especially tertiary amines, are difficult or impossible to degrade, since esterases—i.e., ester-based enzymes—tend, particularly in the case of ALC-0315, to compete with oxidation processes due to its structure, resulting in prolonged bioactive persistence.

Furthermore, it appears biologically plausible that DSPCs—that is, the synthetic phospholipids of LNPs—may, even after degradation, be recycled and reintegrated into the cell membrane, thereby altering the overall membrane structure. In other words: we know almost nothing about the long-term consequences.

I hope that up to this point I have been able to make clear and comprehensible just how complex, unpredictable, and fraught with unanswered questions lipid nanoparticles are, and how they function in principle. And I hope it has become clear why—driven solely by the PCR-test pandemic and regulatory negligence—such an insufficiently researched technology, with potentially severe long-term consequences that we cannot yet estimate in magnitude or probability, was deployed at mass scale in humans. The largest human in vivo experiment in the history of modern medicine was initiated.

If you have been able to follow up to this point and understand at least the essentials, then you will understand why the greatest error lay—and still lies—in treating modRNA and LNPs as separate entities, and why traditional pharmacological notions of a simple “mass × total molecule number equals toxic effect” model fail to apply.

If you wish to understand the details more deeply, I recommend reading both the work by myself, Maria Gutschi, and Dr. Seneff, as well as the paper by Maria and myself that was shown at the beginning of this lecture, where we extensively review all mechanisms and properties discussed here using the current LNP literature.

WOW! Lots of work. I especially like your explanation of liposomes vs LNPs. So important

Thank you. Amazing how the ‘powers that be’ have been and are still playing an extreme form of Russian roulette, with the sole difference that in Russian Roulette the bad luck outcome is predictable….

P.S. did you receive my email in the end?